RhythmOS 4-1: Time Signatures

I’ve been hiding something from you.

You see, if you picked up a textbook on music theory & flipped to the section on rhythm, they’d start by talking about time signatures.

Even the best textbook writers explain time signatures with dry academic descriptions like:

“The time signature is a set of numbers placed at the beginning of a piece of music. The top number indicates the number of beats in a measure, and the bottom number indicates which basic rhythmic value represents one beat.”

All of this is true… but it’s an explanation that only makes sense to people who *already* understand the concept.

That’s why we sidestepped time signatures and just said “most music is based on a recurring pattern of four: 1234 1234 1234, over and over.”

Now that we’ve spent twenty+ lessons exploring the “normal” four-based way of doing things, we’re ready to do two things:

- Talk about time signatures in a practical way, and

- Look at examples of music that *isn’t* based in four.

Time Signatures, Explained

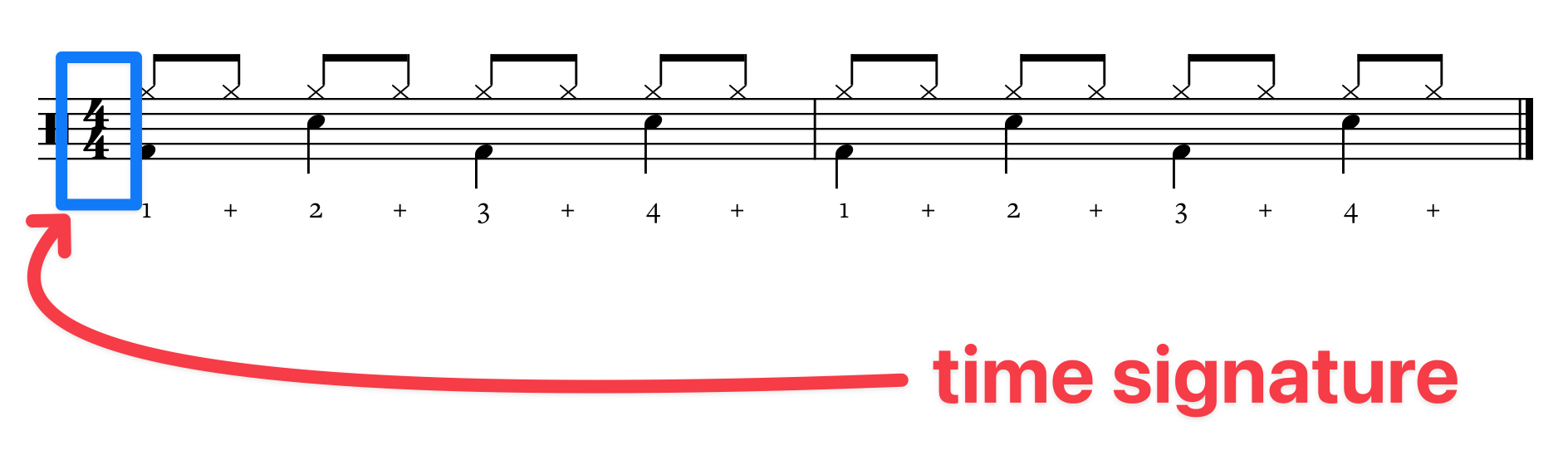

At the beginning of every piece of written music, there are two numbers stacked atop each other:

The top number tells us when the pattern starts over.

Everything we’ve done so far has been “in four”—we count 1234, then start over. 1234, 1234, 1234, etc.

When you’re talking to other musicians, this top number is what you’re referring to:

- “this song is in three”

- “there’s a bar of two”

- “it’s a Rush song, so of course there’s a section in seven”

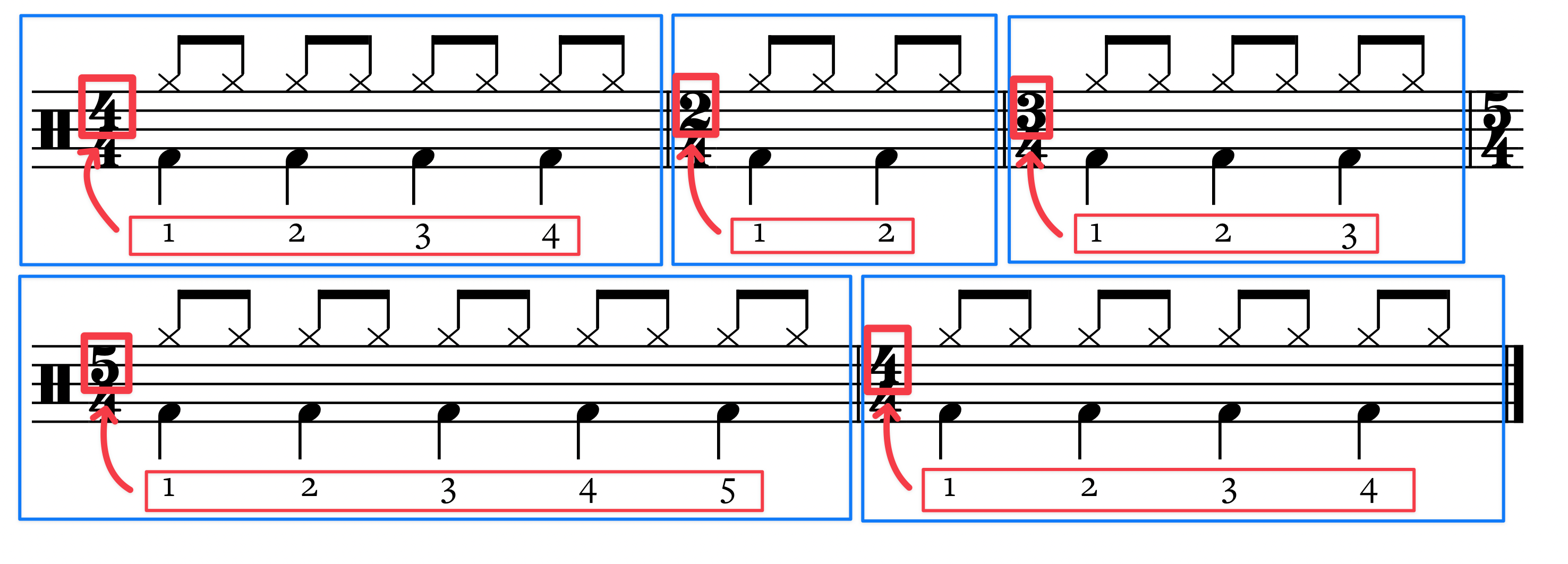

This is an extremely artificial example, but it’ll help you get the idea:

The top number of the time signature tells us how many beats to expect in that measure.

While this example has a new time signature for each measure, time signatures are good until a new one tells you otherwise.

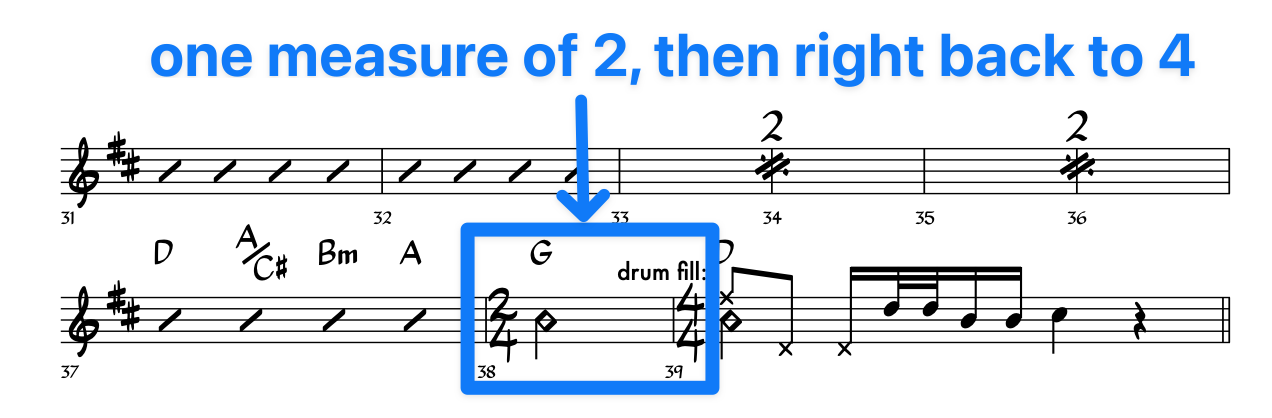

Other times, we’ll leave our main time signature for a single measure:

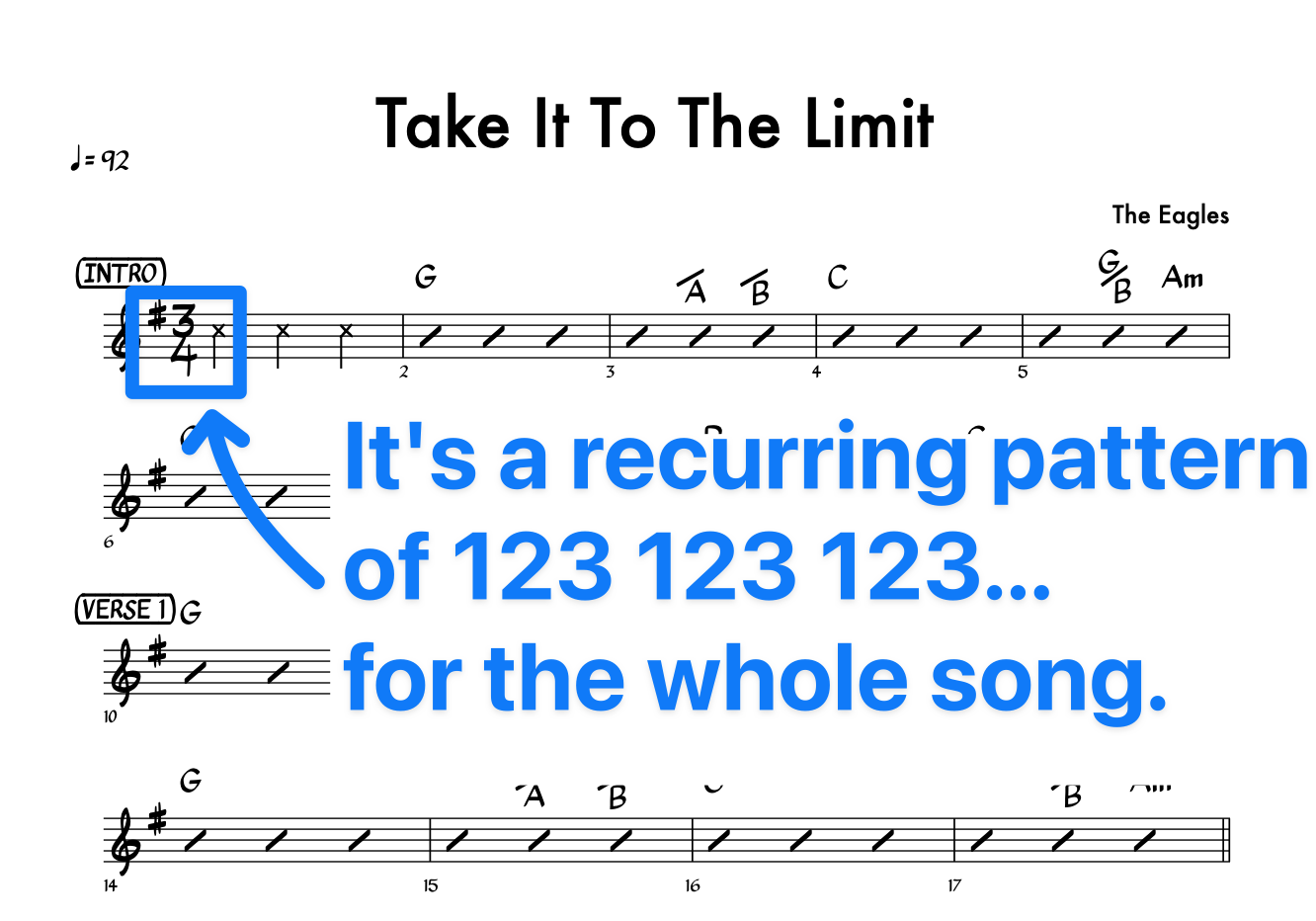

Still other times, we’ll have a whole section that’s in a different time signature:

But what about that bottom number?

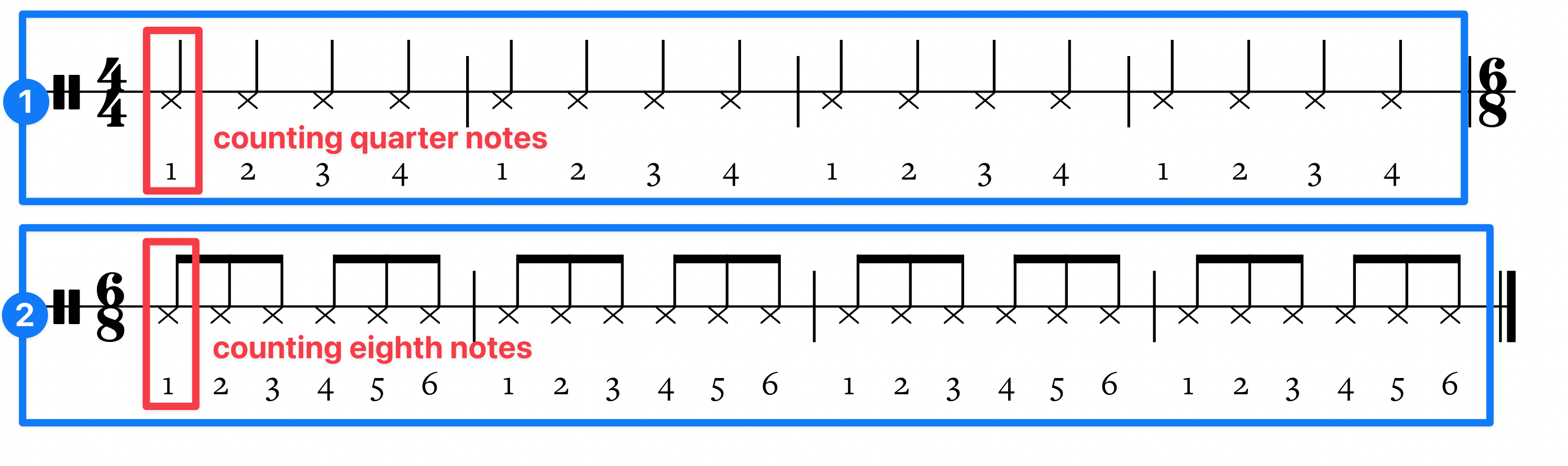

Ah yes—check out that time signature change in Suspicious Minds again:

- When it’s 4/4, we’re counting quarter notes.

- When it switches to 6/8, we start counting eighth notes.

What’s the deal with that?

The bottom number is our measuring stick.

It tells us what kind of note is a numbered beat.

Just like a fraction, think of the bottom number as a denominator.

- If it’s 2, think 1/2 -> half.

- If it’s 4, think 1/4 -> quarter.

- If it’s 8, think 1/8 -> eighth.

Most of the time, the bottom number is 4. So we number the quarter notes.

- 4/4 -> count quarter notes

- 6/8 -> count eighth notes

- 2/2 -> count half notes

Recap

We’re pretty much ready to start looking at examples, but first let’s recap:

- Time signatures are written at the beginning of a piece of music…

- …and anytime it changes to a new time signature.

- The top number tells us how many beats are in each measure.

- 4 is by far the most common…

- …we often use 2 when we want half a measure of 4.

- 3 & 6 are both common…

- …and there are all sort of uncommon ones.

- The bottom number defines our measuring stick—what type of note do we count?

- It’s expressed like the denominator of a fraction:

- 2 in the bottom -> half note

- 4 in the bottom -> quarter note

- 8 in the bottom -> eighth note